D’anciennes consommatrices de drogues aident les consommatrices au Népal

D’anciennes consommatrices de drogues injectables au Népal disent que c'est plus difficile pour les femmes et les filles de se remettre de la dépendance à la drogue.Pour en savoir plus, en anglais, veuillez lire les informations ci-dessous.

Abonnez-vous à l'Alerte mensuelle de l'IDPC pour recevoir des informations relatives à la politique des drogues.

KATHMANDU, NEPAL – “I have lost [the] respect and trust of my family and the community using the drugs,” says a 20-year-old woman with a dark complexion. “But I don’t want other young girls like me to endure what I did.”

The former drug user, whose name is withheld to protect her from the social stigma attached to drug use, is from Lalitpur, a neighboring district of Kathmandu. Influenced by friends, she says she switched from smoking cigarettes to smoking marijuana at the age of 15.

She eventually became addicted. A puff of smoke soon became more important to her than her studies, she says. She then moved on to harder drugs.

At first, it scared her when she and her male friends went to the nearby woods to smoke “brown sugar,” a slang term for an adulterated form of street heroin, rolled in a cigarette. But after trying it, it felt like the earth was moving, she says.

During those days, she felt nauseated and dizzy, with frequent headaches. But later, she started regularly using hashish, brown sugar and heroin.

“I gradually stopped going to the class,”she says.

Though she had become an addict, she didn’t want her three younger sisters to follow in her footsteps. So she used to hide her marijuana and heroin under her pillow, inside a cupboard or in old shoes.

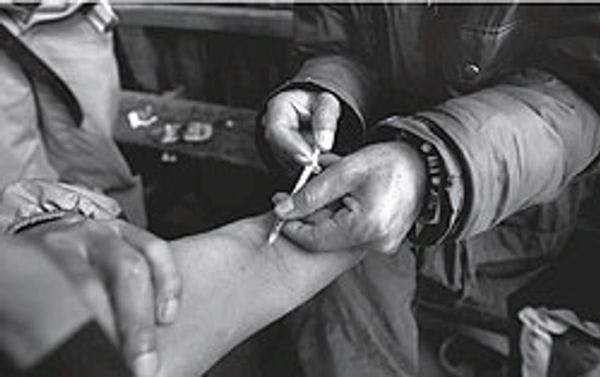

Soon, the 5,000 rupees ($60) her parents gave her as allowance each month was no longer enough to support her drug habit. So she began selling syringes for injecting drugs.

But as her addiction grew, she resorted to sex work as a way to make fast cash. She says she sold her body for 2,000 rupees ($25) to buy brown sugar. And when she was high on drugs, she admits having sexual intercourse without condoms.

Men who found out about her addiction would lure her into bed by promising money or brown sugar, she says. But they would often leave her with nothing.

Two years ago, multiple families approached her father with marriage proposals. But when the boys’ families found out about her addiction problem, they backed out. This encouraged her to take more drugs, she says.

“I started believing that the drug was my friend in my good times and bad ones,” she says.

Abandoned and ostracized, she decided to give up drugs with the hope that she could return to a respectable life. She began visiting the Aavash Samuha Drop-in Center for female drug users near her home in Lalitpur.

It has been four months since she gave up drugs.

She now works as a counselor at the center, a nongovernmental agency that has been working for the rehabilitation of female drug users for more than five years. She counsels women on the risks of using drugs and the possibilities of transmitting HIV through syringes. She assists in the rehabilitation of former drug users and with awareness campaigns.

“At present, I openly work against drug abuse,” she says.

Now she says she wants to make up for lost time with her parents.

“I made my parents very unhappy so far by getting into drugs,” she says. “I want to spend the rest of my life serving them.”

Peer pressure and failed relationships are just a few of the reasons that young women begin using drugs in Nepal. Rehabilitation for girls and women is especially challengning because of a stronger stigma attached to female drug users and the means they use to support their habits,such as sex work. Nongovernmental organizations and drop-in centers are employing former addicts to rehabilitate current users and inspire them to remain drug-free. Still, the cost of rehabilitation and medical problems from drug use remain daily barriers for them.

In 2007, there were 46,309 drug users in Nepal, 3,356 of which were female, according to a survey by the Central Bureau of Statistics of the government of Nepal. Kathmandu alone has 17,458 drug users, according to the same survey.

The majority of female drug users are girls ages 18 to 35 from upper and upper-middle socio-economic classes, says Navaraj Silwal, senior superintendent of the Narcotic Drug Control Law Enforcement Unit of the Nepal Police.

A 17-year-old from the Rautahat district, southeast of Kathmandu, whose name has been withheld to protect her identity, is also a former drug user. She stands in a dark room at the Aavash Samuha Drop-in Center, surrounded by a dozen current female drug users.

Keep up-to-date with drug policy developments by subscribing to the IDPC Monthly Alert.