Nueva Zelanda y su ‘psicolegislación’ sobre sustancias psicoactivas

En 2014, la alarma moral pública y la inquietud política sobre la experimentación con animales se tradujo en una revocación de lo que se suponía que debía lograr la ley neozelandesa para regular el mercado de nuevas sustancias psicoactivas. Más información, en inglés, está disponible abajo.

Suscríbase a las Alertas mensuales del IDPC para recibir información sobre cuestiones relacionadas con políticas sobre drogas.

By Russell Brown

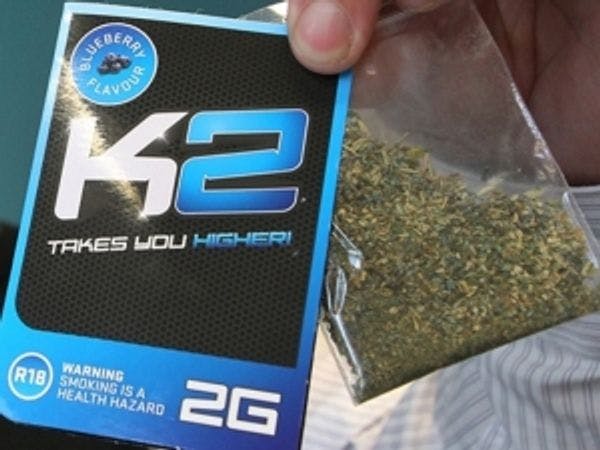

Even as it was making its way to the statutes, New Zealand’s Psychoactive Substances Bill was the talk of the drug reform world. It was seen as a bold, visionary bid to deal with the proliferation of new drugs that fell outside existing laws and address the harms of an unregulated market. It was all the more remarkable that the reform was being championed by a former drug warrior in Associate Health Minister Peter Dunne. When our Parliament passed the Psychoactive Substances Act last year with but a single vote against, it seemed New Zealand had taken a remarkable initiative.

And then, only months into the new world, the government rushed through an amendment that cut off a protracted interim licensing phase, halted the legal sale of all psychoactive substances and made any future approval much more challenging. It happened so quickly that one journalist landed here with a story commission from a major American magazine, knowing reform had been cut short after she’d booked her flights. It is reasonable to ask now whether the new law even has a viable future, given the turn in the political mood. The answer to that question depends on how you ask it.

On one hand, things are falling into place. The long-awaited regulations defining the requirements for manufacturing, importing and research and product approvals were signed off by Cabinet in July and recently came into force. Regulations for wholesaling and retailing approved products are on track for the second half of 2015, in plenty of time for any newly approved product. It appears there will be an industry of some sort prepared to play by the Act’s rules. And the Psychoactive Substances Authority, beleaguered for much of this year, has been moved to a more supportive part of the Ministry of Health.

But there’s an elephant in the room. In rushing through the amendment in May, MPs not only repealed the parts of the original Act providing for interim product licensing, they also added wording that stipulated that “the advisory committee must not have regard to the results of a trial that involves the use of an animal”.

There is an exception: the advisory committee and the authority may act on an overseas animal trial that finds a psychoactive product “may pose more than a low risk of harm to individuals using the product”. But they are forbidden to consider any animal trial evidence in deciding that a product poses only a low risk of harm.

In short, they may only pay heed to evidence from animal trials to ban a product, not to approve it.

“Our overarching assessment, not just in the offices of the Psychoactive Substances Regulatory Authority but also on our expert advisory committee, is that, at this point in time, it is not possible to have a product approved without animal testing,” says Stewart Jessamine, group manager at the clinical leadership and product regulation branch of the Ministry of Health and effectively the personal link between the Psychoactive Substances Regulatory Authority and its new neighbour, Medsafe.

“Obviously, that’s a major barrier to new products entering the market.”

Other interested parties speculated to Matters of Substance about possible workarounds, but as of now, the situation is this: the process created to approve and license psychoactive products – thus taking manufacture and sale out of the hands of the unregulated black market – cannot possibly approve or license any product.

To understand this strange situation, it’s useful to look back on the Psychoactive Substances Act’s difficult infancy.

The interim licensing period provided for in Schedule 1 of the Act was a relatively late addition to drafts of the Bill. From August 2013, it allowed manufacturers to seek interim approval for their existing products until the necessary regulations were published and for retailers to seek their own licences. The thinking was that the Act’s process needed an industry, and that might not happen if the whole market was abruptly outlawed.

But writing the regulations proved tough going. Uruguay is finding the same thing as it tries to get its pioneering regulated cannabis market in place, and its government is only writing for a market that is yet to start. New Zealand’s officials were introducing regulation to a market that had been raging for years. Further, an under-resourced Psychoactive Substances Regulatory Authority failed to perform. It made few decisions, acted slowly and all but seized up from January 2014 onwards.

Click here to read the full publication.

Keep up-to-date with drug policy developments by subscribing to the IDPC Monthly Alert.