Orphans a forgotten casualty of 'drug war'

It was a day just like any other. Lin, a 10-year-old Hmong girl, sat in front of the television for the evening news, along with other children from her village in the hills of Chiang Mai province.The children chatted throughout the whole news programme. They were only waiting for their favourite soap opera to come on after the news.

Suddenly, images from a press conference flashed up on the screen. Police were parading the suspects from a recent drug bust before the media.

Lin (not her real name) glanced at the screen, and spotted someone who looked familiar.

She screamed and cried once she realised that the people who had been arrested were her parents.

With her mother and father in prison and no-one to look after her, Lin headed to Chiang Mai where she scratched out a living selling garlands on the street.

She was eventually picked up by the Volunteer for Children's Development Foundation in Chiang Mai, a non-profit group which helps children in need.

Poj Rungrojkhnlaporn, the organisation's founder, said he first met Lin when she was 12 years old.

''I saw this young girl walking in and out of many bars on Loy Kroh Road trying to sell roses to foreigners. I knew if I didn't do anything about it, Lin may have ended up in the sex trade. I talked to her and found that she had no home.

''Lin is a very quiet girl. I think part of it is because she is mentally damaged from what happened to her parents.

''She is now back at school and is returning to a more normal life. But I don't think the scar in her heart will ever be healed.''

Drug raids are not a new issue for Thailand. In 2003, then prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra announced his controversial ''war on drugs''.

Approximately 2,800 major drug dealers and more than 20,000 lower-level dealers were arrested as a result of Thaksin's policy.

More than 2,500 people were also killed, many by police.

Those who were killed included drug dealers, but also many innocent people who were not granted a trial.

Among those most affected were the thousands of children across the country, like Lin, who were left abandoned after their parents were killed or incarcerated.

Most of the raids were conducted in the northern parts of Thailand on the border with Myanmar. The area is home to many hilltribes, who suffer from poverty and social isolation.

According to Provincial Police Region 5 in Chiang Mai, there is no record of how many people were arrested or killed during the 2003 war on drugs.

Reaching out

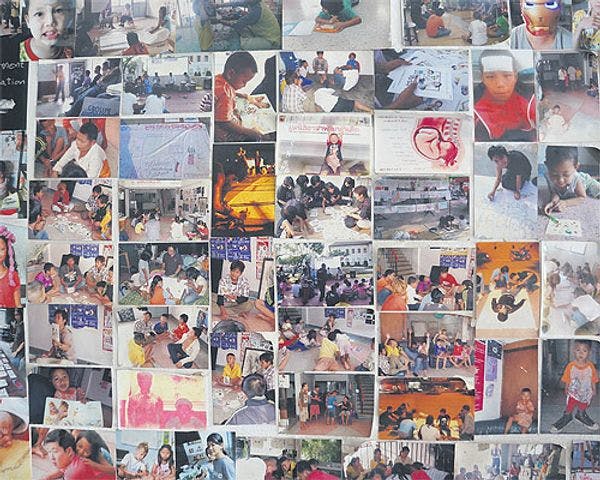

Spectrum had the opportunity to talk with several organisations working directly with children in the north of Thailand. The conversations revealed that every youth shelter in the area has at least three hilltribe children who were left abandoned after the war on drugs. The effects of the policy on their lives has been devastating, with many forced into prostitution or drug dealing to support themselves.

Mr Poj from the Volunteer for Children's Development Foundation, told Spectrum about some of the children he was caring for at the foundation.

''We first ran our foundation as a place where homeless children can go to when they need somewhere to sleep or a place to eat. Most children we helped were hilltribe and Myanmar kids who worked selling garlands on the street,'' he said.

''Once our foundation became more established, a lot more children came to us. Some of them came to stay overnight and left in the morning. Others really had no place to go and ended up staying with us long-term.

''Among these kids [who stay long-term], there are a few who stay with us during the day, then go out at night to work. Some work in restaurants, while some are working in the sex trade,'' Mr Poj said.

''Of all of the kids that are with me, there are two cases that provide the greatest examples of the negative effects of hard-line drug policies,'' he said, and told their stories. Gudea, a 15-year-old Hmong boy, moved to Chiang Mai with his parents when he was very young. They previously lived in Mae Rim district, but moved to the city in pursuit of a better life.

Like the majority of hilltribe people who move to work in a big city, they expected good-paying jobs.

But Gudea's parents struggled to find a job that could bring in enough money to support the family.

After a couple of years living in Chiang Mai, Gudea's family welcomed a new baby girl. Even though the birth brought joy to his family, their financial situation was becoming impossible.

''We didn't have enough money to live on when my sister was born. So my dad told us he would have to find a new job,'' Gudea said.

''After a few months, he started to bring home a lot of money. We had good food to eat, we could afford to buy new clothes, and we even had enough money to send some back to my grandmother.

''For the next year, we had enough to build a small house and buy a second-hand pickup truck. I started to feel like our lives were going to get better.

''But one day my mother told me that my father had been arrested for drug dealing.''

Mr Poj found Gudea three years ago. He was sleeping on the streets, and had no place to go.

''Gudea told me that his mother was also arrested about a year after his father. She had also turned to selling drugs to be able to feed the family.

''After his mother was arrested, the police seized the family's property. Gudea's sister was sent back to the village in Mae Rim long before his mother was arrested. Gudea was left without a home or family,'' Mr Poj said.

''Having no place to go, Gudea joined other homeless kids selling garlands on the street. I took him in and sent him to school, and he helped me with some work at my foundation.''

The parents of Lang, a 17-year-old Tai Yai boy, were also arrested for drug dealing.

''Both of them would work during the day while I went to school. We all came back and would see each other every night. I had such a happy family life,'' Lang said.

''But I came home after school one day and my landlord told me the horrible news. She said both of my parents had been arrested for selling drugs. I was shocked when I heard that.

''My landlord told me to leave the house immediately, since she was scared that no one would ever rent the house again if they knew.''

Mr Poj found Lang two years ago living on the streets.

''When I first found Lang, he was working at a gay bar in Chiang Mai town. It was sad to see someone that young working in the sex trade. So I took him in, gave him advice, and encouraged him to get a better job. I am glad he listened to me and finally got a job as a restaurant waiter,'' Mr Poj said.

Another foundation that is helping children in Mae Taeng district is the Starfish Country Home School Foundation. Originally established to help hilltribe children, the foundation is now expanding to Chiang Mai town, Chiang Rai, and Bangkok to help underprivileged kids.

Richard Haugland, the foundation's founder and president, said that irrespective of whether one or both parents were in jail, it was their children who ultimately suffered the most.

''Some children are lucky enough to have someone look after them after their parents can no longer take care of them. But some are not that lucky and end up being homeless,'' he said.

''We have so many children who are under the care of the foundation. Among these children, there are a lot whose parents were involved with drugs. Once the children stay with us, we take care of them until they can be independent. We are trying to help as many as we can, but we can only help a very small group.''

Hitting the target

Apinan Aramrat, director of the Northern Substance Abuse Centre at Chiang Mai University, said the social problems caused by the 2003 war on drugs are still present and don't seem to be getting any better. The Yingluck Shinawatra government has continued with the hard-line approach to tackling drugs, launching its own ''war on drugs'' late last year.

''The policy set up by the Office of the Narcotics Control Board [ONCB] seems to be the main cause of the problem. I am not sure what the current policy is, but when it was first launched more than 10 years ago, the ONCB just wanted to get rid of drug dealers as quickly as possible without even checking if the person accused was guilty or not,'' Dr Apinan said.

''The ONCB came up with a target number [of drug dealers to be arrested] and sent it out to the police. This is when it gets messy because the police are then under pressure to meet those targets. The result is that there are a lot of innocent people affected by the war on drugs,'' he explained.

''Some really were guilty, but there were also many who had nothing to do with drugs. We have no exact number of how many innocent people were affected, but I know there are many out there.''

But Siriporn Wanawiriya, director of the drug suppression unit at the ONCB, said current drug policies have changed significantly from those of the past, and are now less target-oriented.

''Last year, the ONCB policy for drug suppression focused on the five aspects of drug smuggling, which are production, import, export, trade and possession. Those who fell into one of those categories were arrested. We set a target of 60,000 people to arrest last year, and we arrested 64,617,'' Mr Siriporn said.

''This year, we have changed our approach to make the seizures more effective. We have focused more on pursuing the supply chain. Once we arrest one drug dealer, we will use information gained from that dealer to trace the full distribution network, from the users up to the manufacturers. I believe we will have another good year.''

Ms Siriporn said the ONCB has no policy to deal with the social aftermath of drug arrests.

''Though there are a lot of children and other family members affected by the arrests, we are not the ones responsible for that. The ONCB was only set up to take care of the drug problem. I think social problems have to be solved by other government units who are working directly with that issue.''

''The sad part is that the government spends a huge amount of money trying to get rid of drugs, but no one seems to care about the aftermath,'' Dr Apinan said

''For example, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security is directly involved with this issue. They are the ones who take care of homeless children, but the government doesn't provide them enough funding to work on the problem.

''This is why there are so many NGOs in Thailand helping people with this problem ... that is supposed to be the government's job,'' he added.

Songwit Chearmsakul, from the of Social Development and Human Security Ministry, takes care of homeless people and those who need temporary shelter.

But because of budget constraints, the onus is still on those in need to seek out help by contacting their local office of the ministry.

''We don't have social workers to go around and search for people who have a problem. We don't have the budget for that,'' Mr Songwit said.

''Our main focus is to help children and women who are the victims of abuse. We have records of each person who comes to us, but none of them relate to the war on drugs.''

Time for change

''I think the way our society works is a bit strange. I see a lot of children and family members of convicted drug dealers being abandoned,'' Dr Apinan said. ''It's all because people don't want to get involved with anyone related to drugs even though these family members are completely innocent.

''These people are cast out from society. They have no place to go and no work available to them. Many, especially hilltribe people, end up dealing drugs because it is the only option they are given.

''But the children are the ones who suffer the most. They are stigmatised by society. No one seems to want to offer a helping hand to them since they don't want to get involved.

''That is why there are so many children working at such a young age. Some wander the streets selling garlands, some become prostitutes, and others end up following in their parents' footsteps and selling drugs.

''I think it is about time that our government worked on this problem as part of a broader drug policy. Otherwise there will be no end to it.''

Keep up-to-date with drug policy developments by subscribing to the IDPC Monthly Alert.