chuck holton - Flickr - CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Evidence that cannot be contained: The World Drug Report 2025 reveals the ongoing failure of the drug control regime

Today, the UNODC released its flagship publication - the 2025 World Drug Report. Despite the agency’s best efforts to convey progress, the report is an indictment of the global drug control regime. Data point after data point reveal a systemic failure to contain drug markets and protect the health of people who use drugs.

In a welcome move, the thematic Booklets in this year’s publication explicitly acknowledge the harmful consequences of punitive policies, and their inability to disrupt drug markets and organised crime. However, this recognition is still limited by the UNODC's self-imposed commitment to preserve the current drug control regime, rather than to openly acknowledge the failure so starkly evidenced in its own report.

The divergence between the UNODC's political messaging and technical reporting is problematic, but not new. As the international community embarks on an independent rethinking of the global drug control machinery, the UNODC must provide Member States with an unbiased presentation and narrative around the evidence. UN entities should be honest brokers of information, not spin doctors. Now that Ghada Waly has resigned, the future Executive Director must have the courage to engage honestly with Member States on the failings of the current system.

The official narrative

The World Drug Report always opens with a preface by the Executive Director of UNODC. With Ghada Waly having announced her early resignation a few weeks ago, the lack of excitement is palpable in this year’s text, which mainly lists the growing challenges in illegal drug market

Only one paragraph proposes solutions, and these are but UNODC's traditional priorities: 'Investing in the prevention of drug use at an early age', criminal justice responses that 'focus on disrupting the illegal market', and – more positively – treatment and services that are tailored and responsive to people's needs. Notably absent are harm reduction, human rights, or any reference to the new panel of independent experts that will review the system

There is a real disconnect between the policy prescriptions contained in this paragraph and the contents of this year’s World Drug Report, which question the effectiveness of law enforcement, emphasise the evidence for harm reduction, and highlight the consequences of punitive policies. But let’s start with the basic facts.

Drug use is growing, as are drug-related harms.

The 2025 World Drug Report's main headline is that drug use continues to hit record highs. The UNODC estimates that 316 million people (6% of those aged 15-65) used drugs in 2023, up from 243 million in 2013. Growth is concentrated in cannabis and cocaine use. 14 million people injected drugs in 2023, and half of them are living with hepatitis C.

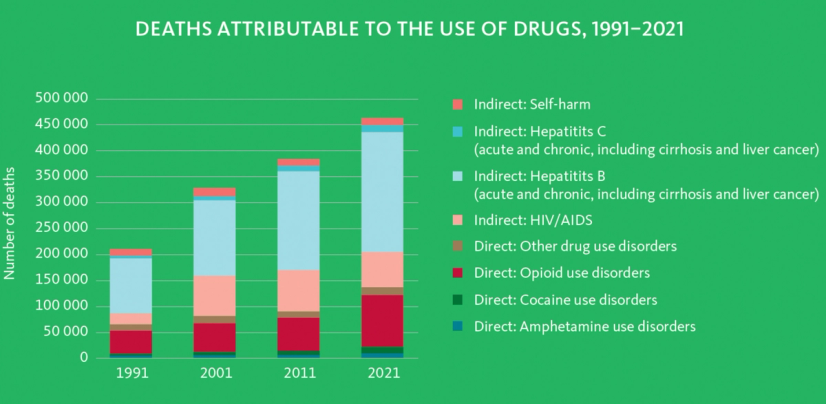

Drug-related deaths increased from over 350,000 in 2011 to over 450,000 in 2021 - unfortunately we lack updated data for later than 2021. An estimated 64 million people experience drug-related problems, a 13% increase over 10 years. Only 1 in 7 men and 1 in 18 women have access to drug treatment. Only 26 of 110 reporting countries provide access to naloxone, and 76 of 133 offer some coverage of opioid agonist treatment.

Credit: UNODC World Drug Report 2025

Law enforcement does not disrupt drug markets, but it can make them deadlier

A thematic Booklet in this year's World Drug Report examines the links between drug trafficking and organised crime. While the topic would appear politically convenient to UNODC - making the case for more investment in law enforcement and drug control - the Booklet contains an illuminating section that assesses the effectiveness of drug responses.

In a nutshell, the Booklet finds that 'drug markets, as a whole, are highgly resilient to law enforcement intervention'. Indiscriminate actions against trafficking, which are 'a common type of drug law enforcement response', leave 'drug trafficking groups largely unaffected'. Additionally, 'drug seizures and arrests can change the market equilibrium, sometimes reducing purities and increasing prices, but never eliminating the market as a whole'.

In fact, the Booklet acknowledges that crackdowns can drive insecurity, as ‘ violence increases only when those at the very top are removed, suggesting that inner-and inter-group conflict emerges from power vacuums’. Additional research suggests that major drug seizures — especially involving synthetic opioids — have been associated with increased overdose deaths.

These conclusions are backed by the data provided elsewhere in the Word Drug Report. For instance, seizures of stimulants such as MDMA have more than doubled in 7 years, from under 300 ton equivalents to over 600. Methamphetamine seizures have also doubled from under 200 ton equivalents in 2017 to over 400 in 2023. But the size of both drug markets has continued to grow, which shows that increasing seizures result mostly from the expansion of production. A message that Member States will need to hear loud and clear during the upcoming review of the global drug control regime.

A technical endorsement of harm reduction – with no political backing

A second thematic Booklet concerns the ‘Impact of drug use’ on people who use drugs, families, and communities. The Booklet may be seen as a reaction to the 2024 thematic chapter on ‘Drug use and the right to health’, as some Member States felt that it was necessary to switch the focus from the right to health of people who use drugs, to the harmful consequences of drug use.

The Booklet opens with the recognition that ‘most of the harms caused by drug use, the impact of drug use and drug use disorders are preventable or can be mitigated by acting on different modifiers’. Thus, the focus of the chapter shifts from preventing drug use in itself, to preventing its harms. In fact, a significant part of the Booklet is dedicated to explaining that drug use does not automatically result in harms, but that those are mediated and shaped by social and political determinants, including class, race, and gender.

The booklet also contains a summary of the very well-established evidence on the effectiveness of traditional harm reduction interventions for drug use. Newer approaches such as drug consumption rooms and sites, drug checking services, and heroin-assisted treatment are also mentioned. In general, the chapter is a complex and nuanced document that reacts positively to many of the criticisms raised by IDPC with regards to last year’s chapter on the ‘Drug Use and the right to health’.

Whilst this is very welcome, the failure once again to explicitly acknowledge ‘harm reduction’ as a holistic, lifesaving approach - rather than a set of technical interventions in response to injecting drug use - continues to hamper the Report and, by extension UNODC itself. It also puts it at odds with the rest of the UN system Common Position on drugs, which wholeheartedly endorses harm reduction, and with the entities and experts that have recognised the harms of drug policies themselves (see, for example, the 2023 report from OHCHR and the 2024 report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health).

Recognising the harms of criminalisation

In a critical development, the Booklet on 'impacts of drug use' recognises that punitive laws and practices exacerbate the harms of drug use. Particularly notable is a direct critique of criminalisation - a very welcome improvement compared to last year’s reports.

Thus, the Booklet notes that 'the criminalization of drug use and resulting incarceration of people who use drugs or have drug use disorders have high costs, both direct and indirect, for individuals, their families and the community.' Additionally, 'Policies that target people in relation to their drug use add to the stigma and discrimination against such people and can also exacerbate the negative impact of drug use on health.' Let us hope that the next UNODC Executive Director to take this recognition from the depths of the report and finally joins other UN entities in calling for the decriminalisation of people who use drugs.

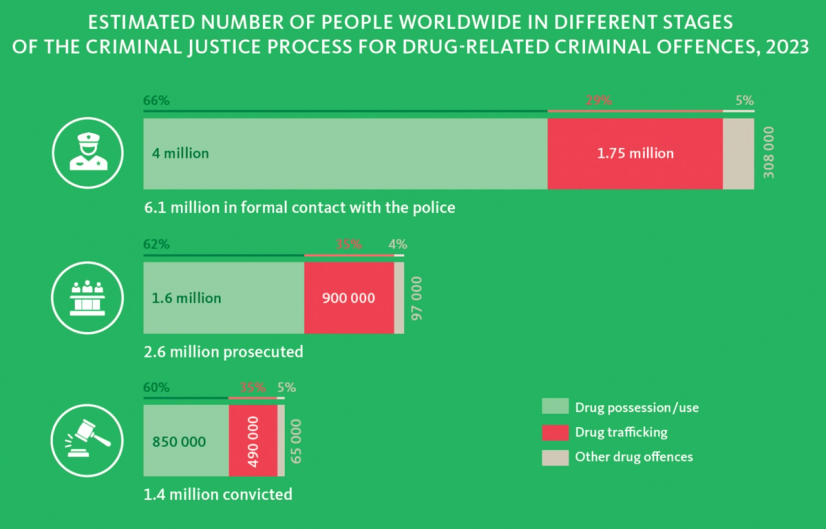

This recognition is important because the punitive thrust of the drug control regime continues unabated. According to new data provided by this year’s World Drug Report, in 2023 6.1 million people were in contact with the criminal legal system for drug-related activities - 4 million for mere possession for personal use. Up to 1.6 million were prosecuted and 850,000 convicted solely for drug possession or use offenses. There can be no doubt that people who use drugs continue to be the main target of the drug control machinery.

Credit: UNODC World Drug Report 2025

Political narratives still permeate the report.

Despite these welcome developments, serious concerns remain regarding the Booklet on 'impacts of drug use'. The chapter's opening framing positions 'drug use' as a driver of societal harms, potentially pitting people who use drugs against their families and communities. While the report acknowledges that social and political determinants mediate harms, this recognition is not consistently applied. For example, at one point the Booklet bizarrely includes the millions spent on criminal justice responses amongst the ‘costs of substance use disorders’.

We are also concerned by claims that 'the children of parents who use drugs or suffer from drug use disorders are also more likely to lack a safe nurturing environment’. Whilst parental drug use may have in some cases impact on the welfare of children, such a generic statement can be deeply stigmatising and harmful in a policy context where many parents - particularly mothers - fear being deprived of parental rights because of mere drug use. It would have been helpful to add a note explaining that, according to existing research, the sole act of using drugs is not harmful to children and should entail no limitation on rights.

Political bias appears elsewhere in the report. For instance, UNODC fails to acknowledge the possibility that the actual aim of legal regulation may be to curb the power of organised crime - as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Turk regularly does. This leaves Member States without evidence on a policy option that could bring success where law enforcement has resoundingly failed.

UNODC remains silent on human rights.

Human rights are completely absent from the World Drug Report, despite the catastrophic human costs of drug policy, well documented by the UN’s own human rights system. Notably, the 2024 World Drug Report had proposed a framework on the right to health and drug use. Whilst that analysis was flawed, it was the first time that the UNODC’s flagship publication touched explicitly on human rights and we hoped it would be continued. It is disappointing to see almost no reference to the right to health in this year’s entire report.

This points to the well documented lack of willingness of UNODC to engage with human rights, which is highlighted in the joint statement released today by 70 civil society organisations calling for UNODC and CND to explicitly and unequivocally condemn the use of the death penalty for drug-related offences.

At a time of global rethinking, we need an honest and unbiased UNODC

In sum, the World Drug Report 2025 provides a good example of UNODC’s contorted position. On the one hand, much of the report details the obvious failings of the global drug control regime, as well as the harms it continues to exacerbate. On the other hand, at a political level the UNODC remains committed to defend the status quo of which it is a central part.

In March 2025, the CND decided to initiate a historical exercise to rethink the global drug control machinery. This process requires accurate, unbiased information. The Colombian delegation noted as much during the debates, telling UNODC that:

‘We don’t want politically correct reports but accurate ones, that tackle developments and problems that we face, so states know then what to do’.

This tall order still needs to be met.