chalermphon_tiam - Shutterstock

Thailand risks reversing successful reforms, repeating drug policy failures

When Thailand’s Prime Minister Sretta Thavisin announced plans to re-schedule cannabis as a narcotic and reduce the threshold for possession of methamphetamine for personal use (not for supply to others) from 5 pills to 1 pill, he signalled a return to drug policies championed over two decades ago. He called for crack downs on people in the drug trade, for people who use drugs to be placed into rehabilitation facilities, and demanded results in 90 days. Success will be measured by an increase in the numbers of people arrested, volumes and value of drugs and assets seized, and numbers of people who use drugs ordered into drug rehab facilities— rather than by any improvements to social, health and other quality of life outcomes for people, e.g. increased access to education, employment and housing, or increased availability of health services such as drug treatment services that are genuinely voluntary. It appears likely that the negative impacts of policing, punishment and criminalisation on individuals and their communities will be ignored.

Reducing the threshold for possession of methamphetamine for personal use, from 15 to 5 then to 1 pill, will drastically escalate the risk of police targeting and arrest, and prevent people who use drugs from seeking drug treatment and harm reduction services for fear of arrest, incarceration and criminalisation. Thailand’s cabinet approved the change on 11 June 2024, yet such outcomes are wholly counterproductive to the country’s National Drug Strategy 2023 – 2027, which aims to implement a balanced drug policy that achieves improvements in human rights, harm reduction and development, in accordance with international standards and commitments such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the 2016 UN General Assembly Special Session on the World Drug Problem Outcome Document. Escalating the punishment of people who use drugs also goes against the recommendations for provision of harm reduction services and decriminalisation of drug use outlined in the UN System Common Position on Drug Policy (2018) and UN Human Rights Council Resolution on human rights and drug policy (2023), as well as the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs resolution that Thailand voted in favour of in March 2024, which focuses on preventing and responding to drug overdose and explicitly supports harm reduction approaches.

Like the horrifically violent 2003 war on drugs, the proposals by Prime Minister Sretta to re-criminalise cannabis and increase the criminalisation of methamphetamine rely on the flawed logic that harsher penalties will deter people from using or engaging in the supply of drugs.

In 2003, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra launched a “war on drugs” with the promise of eradicating drugs from the country within four months. Law enforcement agencies were effectively given a license to kill people suspected of being involved in drug-related activities. After a few months, an estimated 2,800 people had been killed in extra-judicial executions with over 7,000 people injured. There has not been a single prosecution of any person for any of the killings. Like the horrifically violent 2003 war on drugs, the proposals by Prime Minister Sretta to re-criminalise cannabis and increase the criminalisation of methamphetamine rely on the flawed logic that harsher penalties will deter people from using or engaging in the supply of drugs. It places immense trust (and resources) on policing and punishment to solve deep-seated social and economic concerns for which the use and supply of drugs have been made the scapegoat.

There is ample evidence to show that decades of punitive drug policies aspiring for a “drug-free world” have not succeeded in achieving their stated aims to reduce the use and supply of drugs. In addition, the latest report on regional drug trends by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime finds that the price of drugs such as methamphetamine have reached record lows, with the high volume of seizures again breaking records—meaning that scaled up law enforcement efforts from countries such as Thailand have failed to disrupt supply. While widespread corruption and abuses by police are acknowledged, measures to address those abuses and prevent them from being repeated remain at a nascent stage, for example the halting efforts to implement the new law against torture and enforced disappearances. Another important legal reform to note is the Narcotics Code that came into effect in December 2021, which aimed to reduce the crisis of Thailand’s overcrowded prisons (amongst the world’s worst),where people are held mostly for the simple possession and/or consumption of drugs.

Thailand has amongst the world’s highest rates of incarceration for drug offences (over 70% of people in prison are held for drug offences), especially for women.

Thailand has amongst the world’s highest rates of incarceration for drug offences (over 70% of people in prison are held for drug offences), especially for women. It also has the highest prison population rate in Southeast Asia, according to the most recent World Prison Population List (14th edition). The Department of Corrections reports that as of 1 May 2024, there were a total of 287,050 people in prison. Of that total number, 210,851 people (186,927 males and 23,924 females) were in prison for a drug offence, comprising 73% of the total number of people in prison in Thailand. With prisons in the country having an official capacity for 110,000 people, the rate of overcrowding reaches almost 300%. Serious concerns have been raised about the poor conditions of prisons in Thailand.

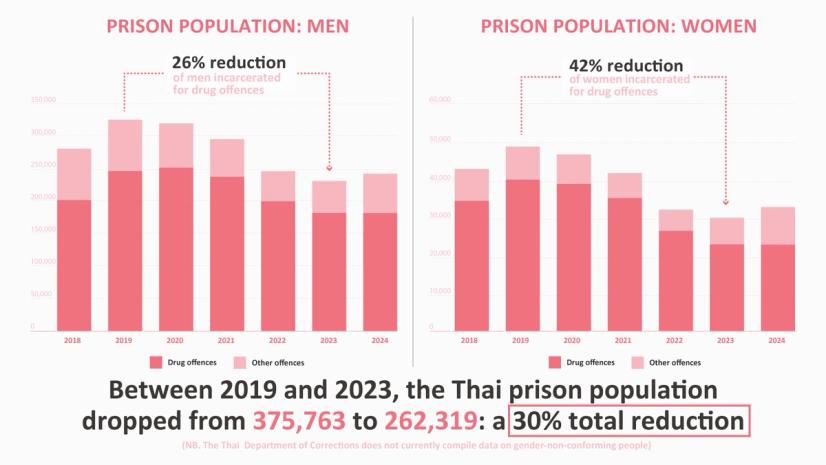

A comparison of the numbers of people in prison in 2024 with 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic) show a significant reduction: from 307,164 imprisoned for a drug offence as of 1 December 2019 to 210,851 people imprisoned for a drug offence as of 1 May 2024. This dramatic drop in numbers, and the decrease in the proportion of people imprisoned for a drug offences indicates the positive impact of a series of drug law reforms that began in 2017 and culminated with the Narcotics Code, which includes substantial efforts to strengthen the health response by ensuring voluntary access to drug rehabilitation programmes and scaling up community-led responses to the provision of drug treatment and harm reduction services.

The drug law reforms that began over 7 years ago further led to a fall in the numbers of people sentenced with the death penalty, falling from 528 people in 2018 to 212 people in 2022 on death row in Thailand’s prisons—although the proportion of people on death row remained around 60% during this period and increased again in 2023. The last execution carried out in Thailand was in June 2018.

The decreases in the numbers of people in prison, including those on death row, in Thailand are notable in the context of an upwards trend in the overall global prison population since 2000. Efforts are still underway to work out the modes of implementation of the various reforms under the Narcotics Code. The meaningful engagement of intersectional communities of people who use drugs will be critical to these efforts, in particular women, including transgender women, LGBTQ+ people and sex workers, as they face entrenched stigma, discrimination and higher risks of violence from police. Their involvement is essential to ensure that Thailand’s health and social programmes are accessible, adequate, and leave no one behind. If the thresholds for possession of methamphetamine use are reduced further and people who use drugs are coerced into drug rehabilitation facilities, people are not likely to seek help from any health or social services when they need it. To enforce the thresholds, government resources and priorities will be focused on policing and prisons, rather than improving much-needed health and social services. Consequently, the numbers of people in prison will start scaling up again, and the level of health harms such as prevalence of HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis C is set to increase.

In May 2024, IDPC collaborated with local and international organisations working on drug-related issues in Thailand to send a letter to the Prime Minister, urging his government to support the ongoing attempts at innovating Thailand’s drug policy by taking steps away from policing and criminalisation, and towards improving social and health outcomes for local communities.

The prime minister has said he wishes to act in the best interests of the people and to adopt innovative approaches to drugs. It is hoped he will avoid repeating the mistakes of past drug policies and rolling back progressive reforms.