Toshiyuki IMAI - Flickr - CC BY-SA 2.0 - https://flic.kr/p/2jyzNdM

'Drug-free world' no more! Historic resolution at the UN spells end of consensus on drugs

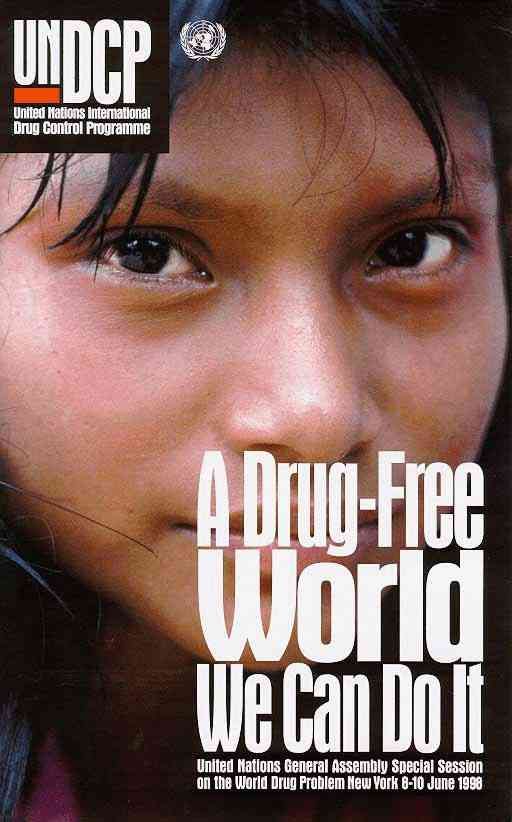

For decades, debates and political commitments on drug policy at the United Nations have been plagued by the goal of 'achieving a society free of drugs' (or 'drug abuse'). Who could forget the slogan of the big UN drugs event in 1998 - “A Drug-Free World, we can do it!”?. This fantastical notion has underpinned unimaginable harm as governments all over the world have strived to eradicate drugs through draconian measures. Despite these efforts, the global market in illegal drugs grows ever larger, more robust and with a greater diversity of substances. In parallel, the human cost of the so-called ‘war on drugs’ continues to grow exponentially - a devastating crisis of mass incarceration, overdose deaths, extrajudicial killings and a litany of human rights violations that have impacted some of society’s most marginalised.

Last week the UN General Assembly made history by adopting a resolution on drugs that did not include the long-standing reference to 'actively promote a society free of drug abuse' for the first time in three decades. Not only was this overly simplistic, ‘war on drugs’-era notion absent from the text, but the resolution includes some of the strongest ever human rights language relating to drug policy, an aspect on which the main UN drug policy forum in Vienna (the Commission on Narcotic Drugs) has made little progress in recent years.

Resolutions on drug policy at the General Assembly have always been agreed by consensus, however this resolution broke new ground as it was adopted - for the first time in history - after a vote.

The Russian Federation, unhappy with the removal of the drug-free language and that the resolution was, in their own words, ‘skewed towards the defence of human rights’ (see minute 32:00 of the debate at the 3rd Committee of the General Assembly in mid-November) called for a vote on the text, which it went on to lose at both the 3rd Committee and the plenary. Thus, the Russian Federation brought about the end of the revered 'Vienna consensus' that has dominated UN drug policy fora, namely the custom of adopting resolutions and political texts on drug policy through the consensus of all Member States, rather than by voting.

It was a reluctant breaking of the consensus with an unprecedented number of countries making statements before the vote in the 3rd Committee, many of them lamenting the need for a vote and noting their hope for a return to the usual consensus for future drug policy resolutions. Ultimately, when the resolution reached the plenary of the General Assembly, a total of 124 Member States voted in favour of the resolution, while 9 voted against, with 45 abstentions.

Mexico, the penholder for this annual resolution on drugs at the General Assembly (normally referred to as the ‘omnibus resolution’ because it seeks to summarise drug policy developments across the UN system) had decided not to simply present the same repetitive, largely agreed text as in previous years but instead took a new approach by cutting its length, regrouping the paragraphs thematically, and placing the focus of the resolution more solidly on the central concern of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs: protecting the ‘health and welfare of mankind’. In their opening statement at the 3rd Committee just ahead of the vote, Mexico's Ambassador to the UN in New York stated: 'Why waste paper on reports and resolutions, which just repeat the same thing every year? We cannot continue with the bureaucratic inertia of transcribing agreed language, and still hope for different results, by repeating our same actions'.

While Mexico's 'zero-draft' was inevitably watered down in the negotiations preceding the vote, the final text marks a serious departure from past resolutions by condemning for the first time in a UN drugs resolution 'systemic racism in the law enforcement and criminal justice systems' and 'underscoring the importance of ensuring that such acts are not treated with impunity'. With respect to the deep-rooted controversy of 'alternative development’ versus forced eradication, for the first time the resolution calls on Member States 'to secure alternative livelihoods, preferably before removing existing livelihoods earned from the cultivation of illicit crops'. In addition, the document also contains strong language on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, in particular a reference to their right to traditional medicines.

The final text marks a serious departure from past resolutions by condemning for the first time in a UN drugs resolution ‘systemic racism in the law enforcement and criminal justice systems’ and ‘underscoring the importance of ensuring that such acts are not treated with impunity’.

Overall, by emphasising human rights concepts and doing away with tired and ultimately harmful ideological objectives such as 'a society free of drug abuse', the resolution goes a long way towards refocusing international cooperation away from reducing illegal cultivation, production and drug trafficking and towards reducing the negative consequences of the global drug situation on individuals and communities.

Crucially, this progressive text was adopted by an overwhelming majority of Member States, with only 9 countries voting against it. This demonstrates that the 'Vienna consensus' has been an instrument to hold back progress on drug policy making, pushing the international community towards policies and narratives that are far more conservative than those of a majority of Member States. A good example of this is that the words 'harm reduction' remain a taboo in international documents, although at least 105 countries support harm reduction in their national drug policies.

It is also worth recalling that the General Assembly is the 'chief deliberative, policymaking and representative organ of the United Nations'. It comprises representatives of all 193 Member States, and it elects the members of the UN Economic and Social Council, of which the Vienna-based Commission on Narcotic Drugs is a functional commision.

This ground-breaking development in New York potentially heralds the beginning of the end of the consensus-based approach to drug policy at the UN, especially given that this follows a series of unprecedented procedural votes that took place earlier this year in Vienna at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs. Russia has been at the centre of these votes, which indicates that opposition to their aggression in Ukraine has left them increasingly isolated at the UN. Broader geo-politics influences all policy issues in multilateral settings and drug policy is certainly no exception. Russia is wedded to zero-tolerance ideology on drugs and actively leads other conservative nations in rejecting any forward progress. Leveraging their isolation in New York has allowed the now persistent and deep cracks in the drugs consensus to widen and accelerate towards breaking point. Whether this fracture will reverberate in Vienna, changing the way resolutions and political documents are adopted at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, is yet to be seen. However, many of us working towards a much more humane and enlightened drug policy hope that this outcome in New York signals the death knell of drug-free goals and the stale and retrograde UN consensus on drugs.

Downloads

Regions

Related Profiles

- United Nations