Cracks in the 'Vienna consensus' reach breaking point at drugs 'omnibus' resolution in New York

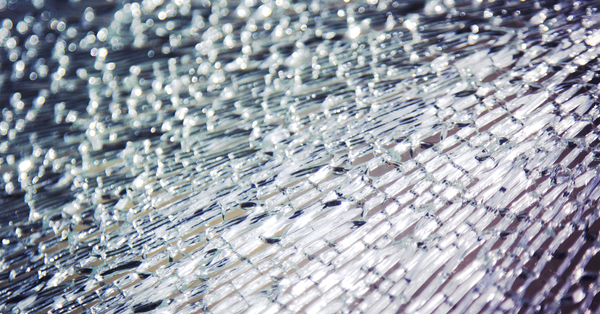

The international drug control system is infamously resistant to change due to what is known as the “Vienna Consensus” – that is, that all resolutions and declarations adopted by the Commission on Narcotic Drugs must be adopted unanimously – even one objection to a paragraph, concept or even a word will prevent the document from passage until agreement can be reached. This system is rarely – if ever – challenged, and year after year, resolutions filled with watered-down agreed language are adopted by the Commission. Critics of the process cite the Vienna consensus as a major factor preventing the natural modernization of the UN drug control treaty system built on the bedrock of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs – making it virtually impossible to alter.

Cracks in this well-trodden system have long been apparent in Vienna but finally reached a breaking point in an unlikely place – New York – as negotiations for the annual resolution “International cooperation to address and counter the world drug problem” (also known as the drugs “omnibus” resolution) came to a close last month.

The drugs omnibus resolution is negotiated every fall in the UN General Assembly’s Third Committee (the committee responsible for social, humanitarian and cultural issues), and then adopted by the full General Assembly in December. As with all multi-lateral processes (particularly in the drugs arena), negotiations around the resolution can get somewhat heated, mirroring the tensions in Vienna around whether to emphasize “zero tolerance” drug enforcement measures or to orient the resolution more towards public health and human rights. Most years, negotiations end with member states relatively satisfied with their ability to come to a consensus with respect to issues on which there is such vast underlying disagreement.

As with all multi-lateral processes (particularly in the drugs arena), negotiations around the resolution can get somewhat heated

But this year was different. Issues debated were not too far from from the usual, with decriminalization and harm reduction entering the debate, as well as support for the WHO Executive Committee on Drug Dependence and various measures around treatment and prevention. But this year two issues caused the ever present tensions to increase exponentially – ‘concerns’ about treaty compliance against the backdrop of Canada’s new cannabis legalization legislation, and recognition of human rights obligations in drug policy.

It was this last issue – human rights – that put the age-old system of consensus to the test; specifically, whether to ‘take note of’ Resolution 37/42 adopted by the Human Rights Council earlier this year, on ‘the contribution to the implementation of the joint commitment to effectively addressing and countering the world drug problem with regard to human rights.’

It was the issue of human rights that put the age-old system of consensus to the test

Normally it would not be a big deal to recognize a process dealing specifically with the drugs issue even if it took place outside of Vienna. However, this Human Rights Council resolution had itself been adopted in a highly contentious process – and by a vote over the objection of several member states. One of the objecting countries was China – who were, to say the least, not happy to see it appear in the drugs omnibus resolution.

And so, in the final session of the Third Committee, the moment before the gavel came down and the omnibus resolution was adopted (and following very stern statements by Russia and Egypt regarding Canada’s ‘flagrant violation of international law’), the Chinese delegate took the floor and – possibly for the first time in the history of the omnibus resolution – explicitly lodged a ‘reservation’ to paragraph 104 of the final omnibus resolution regarding Human Rights Council Resolution 37/42. After the resolution was adopted, Singapore read an ‘explanation of position’ expressing similar concerns.

It is not a surprise that China would object to human rights language. China has always pushed back on human rights in the name of defending state sovereignty, and has been particularly outspoken lately during the Vienna debates on the issue (even recently interrupting a civil society speaker from Amnesty International speaking on the issue of the death penalty.)

It is not a surprise that China would object to human rights language. The surprise is that China chose to explicitly register a reservation to the resolution itself

The surprise is that China chose to explicitly register a reservation to the resolution itself. In a system that takes such collective pride in forcing every possible issue through the narrow eye of the consensus needle, China felt so strongly about the issue that it employed a tool normally reserved only for the most contentious of issues and not normally applied to resolutions (which are non-binding instruments), but to the treaties themselves – such as Bolivia’s famous withdrawal and re-accession with reservation to the article prohibiting the chewing of the coca leaf, or Switzerland’s reservation to the 1988 Convention Against Illicit Trafficking on the criminalization of possession for personal consumption.

So what does this mean for the so-called “Vienna Consensus”? To be sure, ‘cracks’ in the consensus have been forming for quite some time as member states openly take diametrically opposed positions on issues such as the death penalty, harm reduction, and most recently, whether the 2009 ‘drug-free world’ targets should continue for another decade. But it is extremely rare for a member state to explicitly lodge a reservation to a provision in a resolution or other soft-law document before its adoption (so-called ‘explanations of position’, which are read after adoption and which clarify a paragraph, rather than withhold consent to it, are far more common). To lodge a reservation is to explicitly deny consensus with regards to the provision – a stark departure from the practice uniformly followed by member states over the last few decades.

For a system that is so frozen in time as to have recently been labeled “Jurassic” by international law scholars, this departure may just provide the needed passageway for progressive countries to finally move beyond the stone wall of consensus

For a system that is so frozen in time as to have recently been labeled “Jurassic” by international law scholars, this departure may just provide the needed passageway for progressive countries to finally move beyond the stone wall of consensus, towards a more genuine conversation around differing goals in formulating drug policies. Moreover, although it’s unlikely that the reservation will have any significant or immediate effect (for example, it will not appear in the resolution itself, even as a footnote, but rather will be reflected in the summary of proceedings), its effects have the potential to be far-reaching. Its precedential value is itself potentially very useful: how long, for example, before a more progressive member state lodges its own reservation to objectionable language – perhaps on a particularly harsh enforcement provision, or on the old and tired ‘society free of drug abuse’ language? Member states could now even safely rely on this recent precedent to lodge a ‘reservation’ against a renewal of the 2009 Political Declaration targets calling for the ‘significant and measurable reduction and/or elimination’ of drug cultivation, trade and use – which would have far-reaching effects on the next ten years of drug policy. In time, a member state could even lodge a reservation against the repeated and disingenuous reaffirmations of the UN drug conventions in every soft law instrument adopted by the CND.

In short, while the effects of China’s reservation are as of yet unknown, it is clear that a change has taken place. Perhaps it is not that the consensus is broken – as this has been apparent for quite some time – but that member states are finally owning up to the fact that there are some issues on which they simply cannot, and perhaps should not, agree. Recognizing this simple reality could lead the international community towards a more realistic conversation about the many different challenges and objectives around drug policy – which is, ironically, what true cooperation is all about.